We thoroughly enjoyed our visit with Shivangi Patel in April, a medical student from Ohio in the U.S, completing her elective global rotation month with us soon before her graduation. What follows is her beautifully written summary of her visit. Thank you, Shivangi!

Angola Blog – Shivangi Patel

Sections:

1 – The Cavango Clinic 2 – Medicine in the Bushes 3 – Morning Palestras 4 – Unique Cases 5 – My experience as a medical student 6 – Culture of Cavango Clinic 7 – My experience outside of the clinic

1. The Cavango Clinic

The hospital in Cavango was originally built to care for people with leprosy before 1976 before the civil war. Since then, it has been rebuilt and transformed. What began as a small clinic for outpatient consultations and emergency cases with only 3 to 5 patients per week—remained open thanks to a loyal and dedicated staff. About 13 years ago, the Kubackis arrived in Cavango. Speaking with Dr. Tim, he shared that it took years to build trust within the community, which had previously relied on government hospitals or spiritual healers for care. Through consistent, compassionate treatment and word of mouth, more and more patients began to seek help at the clinic. As the demand for services grew, so did the need for a larger space. Over time, the facility expanded into the hospital it is today.

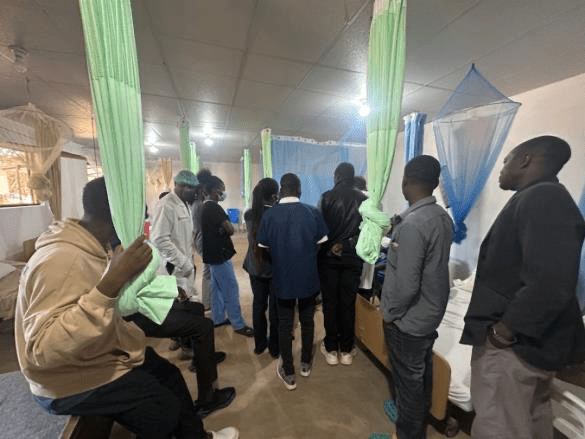

Now, it’s a 120-bed hospital with inpatient wards, an ICU, an emergency department, a maternity room, and four outpatient consultation offices. There’s also an airplane available to transport patients to the city for surgical cases when necessary. A general surgeon and an ophthalmologist visit periodically to provide specialized care, and the hospital is currently recruiting a dentist to join the team. In addition, the hospital includes both outpatient and inpatient pharmacies and a cantina where patients and staff can purchase food and medical supplies. In keeping with Angolan culture—where families typically cook for their hospitalized loved ones—a ‘villa’ was built. These apartments allow families to stay close by and prepare meals during their loved one’s hospital stay. Many of the current hospital staff travel from cities located more than four hours away, so an apartment building has been provided for them to stay in while they are working.

Daily flow:

- Morning rounds on critical patients

- Palestra – public health education to community

- Inpatient consults • Outpatient consults

- Evening rounds

My thoughts:

Walking through the hospital grounds and hearing its history filled me with admiration. I was struck by how a once-tiny clinic serving just a handful of patients a week has grown into a lifeline for an entire region. What resonated most with me was Dr. Tim’s story about building trust over years—how healing is not just about medicine, but about showing up, listening, and caring consistently. They aimed to build a hospital equipped with all the essential resources and tools to provide quality care, while keeping it simple enough to create a comfortable and familiar environment for the local community. Their goal wasn’t to make anything fancy, but rather something that felt like home. I was genuinely impressed by how different the hospital system is from what I’m used to in the U.S.—there’s a simplicity to it, yet it’s remarkably effective. It was eyeopening to see how resourcefulness and community support can create a healthcare system that works beautifully for the people it serves. Seeing the families in the villa, cooking and staying close to their loved ones, reminded me of the deep interconnectedness of health, family, and culture. It made me reflect on how healthcare in underserved areas requires not just clinical skills, but also cultural sensitivity, patience, and long-term commitment. This place is more than a hospital—it’s a testament to what compassionate, community-rooted care can become.

2. Medicine in the Bushes

As one can imagine, practicing medicine in the bush of Angola is quite different from what we’re used to in the United States. It brings you back to the core of medicineclinical reasoning, careful observation, and thoughtful decision-making. Here, you’re constantly weighing the risks and benefits of every test and treatment. This is truly poverty medicine, where cost and burden on the patient and their family are always part of the equation. Some patients travel for days to reach the clinic, many of them on foot. They are incredibly resilient people, and the effort it takes for them to come means they are truly unwell. It’s a humbling reminder of both their strength and the responsibility we have to care for them with purpose and respect.

There are several lab tests available in Cavango that we commonly use in the U.S.—such as CBC, BMP, LFTs, TSH, creatinine, and urea—but they are only ordered when absolutely necessary. In the States, these are often routine and frequently overordered: once upon admission and daily for inpatients. Here, we only run these labs if the results will directly impact the treatment plan. The focus is on minimizing cost for patients, as expenses can quickly add up and become a heavy burden. Every test must serve a clear purpose and offer benefit.

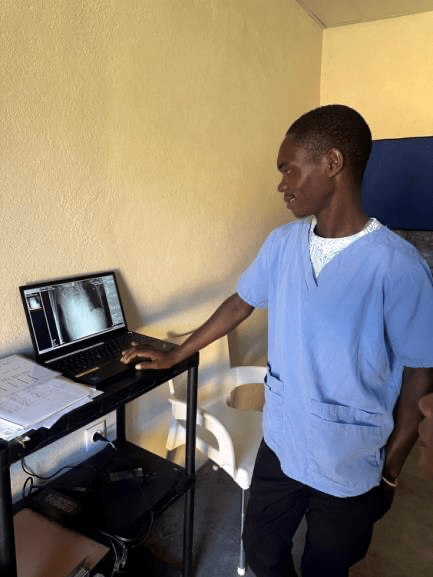

When it comes to imaging, ultrasound is an incredibly valuable tool. It’s used during nearly every patient consultation because it provides a wealth of diagnostic information in a quick and cost-effective way. A new X-ray machine has been introduced at the hospital, but it’s used sparingly—only a few times a month—due to the high cost for patients. Like the lab tests, it’s reserved for situations where it can meaningfully aid in diagnosis and alter the treatment course.

There is also a blood transfusion protocol in place, most often used for children with hemolytic anemia caused by malaria. Only whole blood is given, and it’s collected on an as-needed basis. One of the most touching things I’ve witnessed is the hospital culture that Dr. Tim has cultivated—if a patient’s family member is not a blood match, hospital staff frequently volunteer to donate on the spot. It’s an incredibly beautiful and selfless act of solidarity.

With limited resources, you’re constantly challenged to think creatively and make the most of what’s available—especially in critical moments. Over time, this environment forces you to sharpen your clinical instincts and become more adaptable. It’s a powerful kind of training that you can’t get in a resource-rich setting.

My thoughts:

This experience has deeply shifted the way I think about medicine. Practicing in such a resource-limited setting has reminded me of the importance of treating each patient as an individual—carefully considering their context, their needs, and what will truly benefit them. I’ve been amazed at how much can be done with so little, and how strong clinical judgment, sharpened physical exam skills, and thoughtful decisionmaking can go such a long way. For example, one thing that was particularly shocking to me was the availability of an X-ray machine—but how rarely it’s actually used. Coming from a background in Western medicine, I’m used to seeing nearly every patient receive a chest X-ray upon arrival to the emergency department, and daily chest X-rays for those with severe pneumonia or on ventilators. Here, I’ve learned that many of those practices aren’t always necessary and can often be a waste of limited resources. Instead, clinical symptoms, physical exams, and patient progress are used to guide treatment decisions. It’s been eye-opening to realize how much you can rely on your clinical skills, and how effective medicine can be when it’s guided by thoughtful judgment rather than routine imaging. It’s empowering to see how confident and decisive you become when you rely more on your clinical reasoning than on tests. As I return to the U.S. to begin residency, I hope to carry this mindset with me—to be more intentional, more resource-conscious, and to never lose sight of the human being behind every test and treatment plan. This kind of medicine has shown me the beauty of simplicity and the power of thinking critically with whatever tools you have in front of you.

3. Morning Palestras

Every morning after rounds, everyone gathers outside for a one-hour palestra—a vibrant and meaningful group discussion that brings together patients, their families, hospital staff, and community members. These gatherings begin with a few religious songs sung in local tribal languages, setting a reflective and unifying tone.

The first part of the palestra focuses on spiritual well-being. A short teaching is shared, centered on a passage from the Bible, followed by open dialogue and questions. It’s a powerful moment of connection and encouragement. Many of the people are grateful for this space, especially since opportunities for such engagement are rare in their remote villages.

Next comes the medical education segment. These discussions revolve around common illnesses in the region that affect both children and adults—ranging from preventable conditions to serious, life-threatening diseases. Topics we covered during my time included tuberculosis, hypertension, back pain, tetanus, and even dental hygiene. Each session outlined symptoms to look for, modes of transmission, when to seek help, treatment options, and preventative strategies.

What stood out to me the most was the eagerness of the community to learn. The discussions were dynamic and thoughtful. People asked insightful questions, shared personal experiences, and actively participated. It was clear that these sessions were not only informative but also empowering. The palestra became more than a lesson—it was a shared journey toward better health and stronger community ties.

My thoughts:

Being part of the palestra tradition was very cool, to witness and participate in a practice that blends spiritual reflection with practical health education so meaningfully. In these rural communities, where formal education levels are often low and access to information is limited—no internet, no cell service—this gathering becomes a vital source of knowledge. Unlike in the U.S., where people can quickly search their symptoms online and access basic medical information, the people here rely on these daily sessions to learn how to care for themselves and their families. It’s their version of public health education, and it makes a real, direct impact. When I mentioned to one of the Angolan staff members that we don’t have palestra meetings back home, she was genuinely shocked and asked, “How do you talk to the patients?” That moment made me reflect on how much we sometimes take our resources for granted. I also appreciated the spiritual talks—there’s always something powerful and grounding in the stories they share. The lessons in those moments stay with you.

4. Unique cases

I wanted to share some of the unique cases I encountered during my time in Cavango.

Tetanus:

One day, a 7-year-old boy came into the clinic with a complaint of a stiff neck. He had classic nuchal rigidity—a textbook sign I had only read about until now, and it was incredible to see in person. Based on this, we initially suspected bacterial meningitis and admitted him to the ICU to begin treatment.

Later that evening during rounds, we conducted a more thorough exam and realized something important: all of his muscles were rigid—not just his neck. The rigidity in his abdominal muscles was the key finding that led Dr. Tim to shift his concern from meningitis toward a diagnosis of tetanus.

Back in the States, we would have quickly performed a lumbar puncture and run a CSF analysis to confirm or rule out meningitis. Unfortunately, we didn’t have that kind of lab support available here. So, we moved forward based on clinical judgment and began treating for tetanus as well, adding corticosteroids and muscle relaxants to his care.

Thankfully, the tetanus didn’t progress further. He had no signs of respiratory distress or shortness of breath and was still able to eat and drink, even though his jaw was noticeably stiff. Each day, he improved—his rigidity lessened, his strength is returning, and soon, he was walking again. It was a powerful reminder of the importance of sharp clinical skills, especially in resource-limited settings.

Atrial Fibrillation: When Resources Are Scarce, Creativity Becomes Critical

A 50-year-old male came into the clinic with dyspnea, shortness of breath, and palpitations. On exam, his extremities were cool to the touch, he had a very faint pulse, and noticeable edema. Since we are resource limited and do not have access to a 12lead EKG machine, we performed a quick bedside ultrasound revealing a heart arrhythmia and tachycardia, which we initially suspected to be atrial fibrillation.

Fortunately, the hospital had recently acquired a cardiac monitor—something we don’t take for granted in this setting—so we quickly connected him. The rhythm confirmed our suspicion: atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response (RVR), with his heart rate spiking between 200–250 bpm and occasionally jumping into supraventricular tachycardia (SVT).

With no access to cardioversion and extremely limited medication options, we had to rely on clinical judgment and resourcefulness. The only cardiac medications available were atenolol, amlodipine, and digoxin, so we started him on those immediately. Despite our efforts, his heart rate remained dangerously high throughout the day. We brainstormed, trying to think of any other options.

The next morning, his heart rate was still in the 200s. That’s when we discovered an emergency kit tucked away—almost forgotten. Inside, we found a few vials of adenosine and amiodarone. It wasn’t much, but it was something. We administered them and also increased his dose of amlodipine. By the end of day two, his heart rate was fluctuating between the 120s and 180s, still in atrial fibrillation.

Then, on day three, something remarkable happened—he spontaneously converted back into normal sinus rhythm, with a stable heart rate in the 80s. His symptoms steadily improved, and before long, he was well enough to be discharged. This case was a powerful reminder of how critical adaptability and teamwork are in this setting.

Malaria/Tuberculosis/Measles: A New Normal: Facing Diseases Rarely Seen Back Home

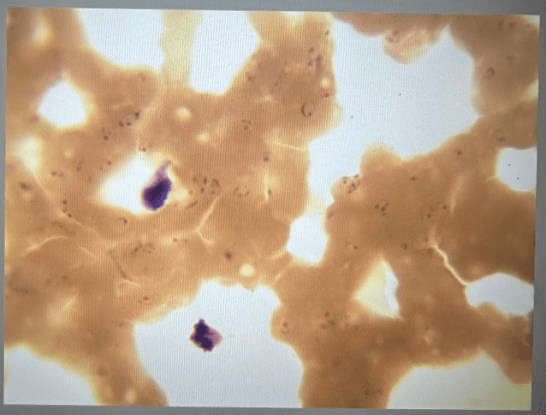

Almost every patient I saw during my rotation tested positive for malaria—especially during the rainy season, when every patient routinely gets a rapid malaria test. Here, malaria is as common as the flu or strep throat back in the States. What initially shocked me was just how normalized it is in daily clinical practice.

I was also struck by how prevalent tuberculosis (TB) is in this region. Because of its high disease burden, TB is always on the differential—you simply can’t afford to miss it or delay treatment. After a month of seeing it so regularly, I realized how desensitized I had become to something that once seemed rare and alarming. It’s wild to think how quickly that shift in perspective happened.

Another surprise was seeing several children diagnosed with measles—something we rarely encounter in the U.S. due to routine vaccinations. But in many of these remote villages, access to vaccines is limited and lack of knowledge, making outbreaks more likely. This experience reminded me how diseases we consider rare or eradicated in one part of the world are still part of everyday life in another.

My thoughts: Reflection from the Field

This rotation has opened my eyes to just how different—and challengingmedicine can be in a resource-limited setting. Diseases like tetanus, malaria, tuberculosis, and measles are not only common here—they’re expected. Some of these conditions are so rare in the U.S. that I realized how little I actually knew about them beyond textbook definitions. I found myself confronted with unfamiliar symptoms and presentations, unsure of the full clinical picture, and even more uncertain about the step-by-step management and long-term consequences. It was humbling to realize that there are still so many gaps in my knowledge.

The case of the young boy with tetanus was especially striking. I had never seen such clear muscle rigidity before, and without lab confirmation, we had to rely entirely on our clinical judgment. It taught me to think critically and trust careful observation. Similarly, the patient in atrial fibrillation w/ RVR was a pivotal moment. He was truly on the edge—his heart racing between 200–250 bpm with no cardioversion or standard medications readily available. It was one of those life-or-death situations where you either find something that works or the patient doesn’t make it. We used every available resource we could find, digging through emergency kits and thinking outside the box just to keep him alive.

These cases reminded me that medicine is not always clean-cut or protocol-drivenespecially not in places like this. It’s often messy, urgent, and deeply reliant on teamwork, improvisation, and a willingness to learn quickly. I’m leaving this experience not only with more knowledge but also with a much deeper respect for the kind of medicine practiced in under-resourced areas. It’s where true clinical grit lives.

5. My experience as a medical student

My month-long rotation at the hospital in Cavango was nothing short of transformative. Despite not knowing Portuguese, I made a conscious effort not to let the language barrier hinder my experience. Through gestures, shared smiles, and genuine curiosity, I was able to form meaningful connections with both patients and staff. I’m incredibly grateful to Dr. Tim, Vianne, and Jordan, who not only welcomed me with open arms but also graciously translated everything for me throughout the month. Their kindness made a great difference in my ability to learn and engage fully in the clinical environment.

I even tried learning Portuguese during my time there. I’m far from fluent, but picking up on common phrases and learning new words was fun—and I think the effort was appreciated. In return, I tried teaching some English. Many people were enthusiastic to practice and loved learning new languages, which led to a lot of shared laughs, language exchanges, and even inside jokes. This mutual curiosity and openness created a warm, welcoming, and fun environment that made every interaction more meaningful.

One of the most impactful aspects of my time in Cavango was the hands-on ultrasound experience. Prior to this rotation, I struggled to interpret ultrasound images. Now, I feel far more confident in this skillset, having had the opportunity to perform and interpret all of the ultrasounds during my time there. Dr. Tim’s patience and dedication to teaching were key to this growth, and I’m very appreciative of the time he took to walk me through each scan.

I was also fortunate to be involved in a range of procedures including thoracentesis, paracentesis, intraosseous (IO) access on infants, ultrasound-guided IV placement on patients with difficult access, abscess drainage, and cervical checks. These opportunities offered hands-on experience that is rare for a student and were invaluable in my clinical development.

One challenging aspect of the rotation was the low patient volume during my stay. This wasn’t due to a lack of illness in the community, but rather the inaccessibility of the clinic for many villagers. Heavy rains had caused the river to overflow and destroyed the walking bridge, cutting off access for numerous people living on the other side. It was difficult to realize that many were likely suffering in silence, unable to reach care.

From a student perspective, fewer patients meant fewer clinical cases to observe and learn from—but it also allowed for deeper, more intentional learning with each individual patient. I had the chance to slow down, thoroughly understand cases, and connect more with the people around me. In this space, I also found time for spiritual reflection and growth, which became an unexpected part of the experience.

This wasn’t my first experience working in an underserved or global setting, but it reminded me why I’ve chosen this path. Overall, this rotation was an incredible blend of clinical learning, personal growth, and spiritual connection. I return with greater clinical confidence, especially in ultrasound and procedures, a deeper appreciation for cross-cultural care, and a renewed sense of purpose in serving underserved communities. I plan to bring all these new skills with me into residency and beyond. I left Cavango with a full heart and happiness, carrying unforgettable memories and new friendships that I will always cherish. Though it was hard to say goodbye and I am already missing it, I know I’ll be back to Cavango one day.

6. Culture of Cavango Clinic

One of the most powerful aspects of my time at Cavango Hospital was witnessing and becoming a part of the incredible culture cultivated by the staff. I was met with warmth, kindness, and a sense of inclusion. Despite the language barrier, I felt immediately welcomed.

The staff at Cavango are some of the most hardworking and dedicated individuals I have ever encountered. They work tirelessly—often long hours and overnight shiftsyet always greet each day with a smile. Their energy is positive, joyful, and uplifting, and it was refreshing to be surrounded by generous spirit. What struck me most was their willingness to give so much of themselves, even as many of them work hours away from their families and see them only rarely. There was never a complaint, never a moment of bitterness—just steady, compassionate commitment to their patients and to each other.

What inspired me even more was their eagerness to learn. Every staff member, regardless of role, embraced every opportunity to grow. During rounds and palestras, questions flowed freely—not just from clinicians, but even from non-medical personnel who often joined in simply to listen and absorb knowledge. It was beautiful to witness such a strong culture of learning, where curiosity and humility were celebrated and where teaching was shared with joy.

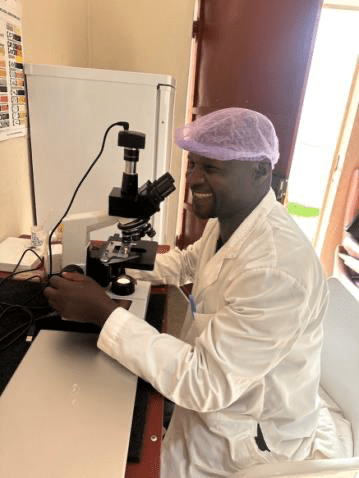

The staff at Cavango Hospital went above and beyond in sharing their knowledge and welcoming me into their day-to-day work. They were more than happy to show me around the hospital and teach me about their specialties with patience and enthusiasm. I spent time in the lab and they walked me through how to determine blood group types using well plates and the process of identifying agglutination—something I hadn’t revisited since early on and had completely forgotten. They also taught me how to examine malaria blood smear slides under the microscope, which I had only ever seen in textbooks until now. I even had the chance to shadow the dentist, who allowed me to observe as he performed dental blocks and extractions, explaining each step of the process along the way. It was incredibly rewarding to see how eager everyone was to teach and how proud they were to share their areas of expertise. Their generosity and passion for their work made every interaction a valuable learning opportunity.

Watching their kindness, dedication, and genuine hunger to grow was moving. It reminded me why I chose medicine in the first place. The environment was a contrast to what I’ve become used to in many U.S. hospital settings, where burnout often manifests as exhaustion and disengagement. In Cavango, despite immense challenges and limited resources, there is still passion, gratitude, and joy—a breath of fresh air.

One unique and beautiful aspect of the care at Cavango Hospital was the way clinicians prayed with their patients. This was something entirely new for me, and I found it incredibly moving. The team would often pause to pray—offering comfort, hope, and a sense of peace that extended beyond medicine. It was heartfelt and personal. Witnessing this integration of faith into patient care was a powerful reminder of the importance of treating the whole person—not just the illness. Even though I’m not used to seeing this in clinical settings back home, I genuinely appreciated the space it created for connection, vulnerability, and healing. It added a spiritual depth to the work that made the care feel more human, more compassionate, and more complete.

The cross-language learning created meaningful moments of exchange—teaching one another, laughing over new words, and forming real bonds that exceeded the barriers. This spirit of openness and mutual respect only deepened my admiration for the team I had the privilege of working alongside.

Being part of the Cavango hospital culture didn’t just shape my experience as a student—it left a lasting impression on who I want to be as a physician. Their example will stay with me as I begin residency and carry forward this renewed perspective on what truly matters in medicine.

7. My experience outside of the clinic

Outside of the hospital, I was fortunate to experience the rich culture of Cavango and embrace so many new experiences. I spent much of my free time with the Kubackis (& Ruby), who were truly wonderful company. Betsy and I shared most evenings reading books, playing Sequence, chatting endlessly, or laughing while online shopping. She even gave me a few driving lessons and taught me the basics of driving a manual stick-shift car—something I had never done before! We had a few bonfires under the night sky full of stars, which was so beautiful. I visited the river a few times and enjoyed peaceful walks around the village, taking in the natural beauty and daily life of Cavango. Also, watching the small aircraft take off and land was really cool.

Some of my favorite memories were spent with the kids next door, Salomé and Judá, missionary children who live in Cavango. They eagerly welcomed me into their world—taking me fishing for the first time (and I even caught a fish!), giving me motorbike rides, and letting me watch as Judá skillfully de-skinned a snake. I also got to learn a bit about coffee farming thanks to Marijn’s family, who grows and roasts their own beans. He showed me the process and sent me home with some freshly roasted coffee, which was such a treat. We often had dinner nights with our neighbors, and I always enjoyed spending time and having conversations with Noortje, Marijn, and their kids. They are a wonderful family.

One especially touching experience was visiting a local family in the village. They warmly welcomed us into their home, and though it was humbling to see the conditions they live in, their joy and hospitality stood out to me. Despite having so little, they expressed gratitude and happiness. I also grew close with many of the hospital staff, who kindly invited me to watch their soccer games. I’d walk over and sit on the sidelines, chatting and laughing with everyone—it was such a fun environment, full of good energy.

One of my favorite simple joys in Cavango was spending time on the swings. I loved how something so small could bring people together. I often invited others to join me, and we’d end up laughing, chatting, and just enjoying the fresh air and each other’s company. Some of them mentioned they had never been on swings before, but once they tried it, they were smiling and enjoyed it. It became a small but special part of my day—carefree moments that felt light and happy.

I also attended church every Sunday, which was one of the most joyful parts of my time in Cavango. The services were full of lively singing in tribal languages—songs so catchy and full of life that you couldn’t help but want to stand up and join in. I was especially grateful to experience Easter there—it was beautiful.

Every day offered a chance to connect, learn, and grow. I spent time getting to know people, learning about their lives, and gaining a deeper understanding of the culture. I enjoyed trying new things and tried to make the most of every opportunity. The people, the place, and the memories I made have meant a great deal to me. My time in Cavango was unforgettable.

Thank you, Shivangi, for sharing such a moving reflection on your month in Cavango. Your observations beautifully highlight how resourcefulness, deep human connection, and clinical humility can transform healthcare in underserved settings. At CANsupport.org, we’re inspired by the trust and care cultivated through community, simplicity, and compassion—values that shine through every scene you described. Truly, medicine is as much about people as it is about tools.